It was very southern. A sunny morning in early spring, April 2, 2022 and a couple of hundred of us gathered beneath the greenie boughs with the mockingbirds singing in Atlanta to say goodbye together to our friend Lucinda Bunnen. She left our earthly bounds the week before to travel to her next adventure. It was a Robert Altman like scene Lucinda would have loved. Round tables with white linen and all of us sporting smiles and drinks and teary eyes as we hugged and shared Lucinda stories and celebrated together her life and our good fortune to have known her.

At 92 Lucinda parted from us with too numerous to count exhibitions, books and accomplishments left in her wake, but the true depth of her impact was gathered there - her people. This assembly was her ultimate treasure, the forever shifted lives of her family and friends and community because we had the simple happy good luck to be born into a realm that included this human creative comet - Comet Lucinda.

Comet Lucinda began streaking across the skies in 1930 and if any life and after-life is likely to continue into interstellar space it is hers. The appearance of a comet is called an apparition - that’s how her movement into my life felt and judging by the range, depth and quantity of friends she drew to her and lifted up I was not alone in that. I won’t tick tock here all her brilliant achievements and attributes. It is well presented in the Atlanta papers, on her website and documented in numerous places besides. I’ll let you do your own research.

What I do want to speak about here is her impact on me personally and how the possibility for each of us to enjoy a healthy and engaged life in art and more broadly how a community’s art and cultural ecosystem is created, sustained and enriched by the lives of certain extraordinary women.

And Lucinda makes me think about how the outsized contributions of a few make all the difference for the many. I want to briefly make the case here that while it definitely ‘takes a village’ to make and grow an art scene that flourishes in the individual lives of a community - it also takes the occasional GIANT. Giant comets.

Ironically, giants and comets come in all shapes and sizes but we know them when we see them. And most, like Lucinda, go humbly - if not always quietly - and energetically about their protean projects, not to make themselves the center of attention, but all the while spinning out universes of new possibilities. Like the moon we just assume that it will come up and we will see it and be enlightened and charmed by it. It is a kind of ‘we can count on this’ feeling. We could and we did count on Lucinda in large and small ways. She became a powerful fixed and guiding part of the firmament.

Setting aside all she accomplished with her family and in the not-art-per-se realms of her life and focusing here just on what she brought forth in art and its communities we see at once that she was a triple threat. As an artist, collector and philanthropist she stands sans pareil.

As a potent philanthropist for the arts and civil rights she founded, furthered and supported through her foundation the Lubo Fund many of the arts institutions in Atlanta that have had lasting impact. A co-founder in 1973 of Nexus - the mighty arts press that became the Atlanta Contemporary Arts Center she brought both her knowledge, talent and excitement about art and photography to it as well as financial and leadership support. It often seemed that Lucinda knew everyone and was everywhere to see, show and share what there was to take in and do. Revisiting her website to write this remembrance I was thrilled to be reminded of how many lives can be touched in a half century of photography and engagement with art and culture when it’s done by a Lucinda.

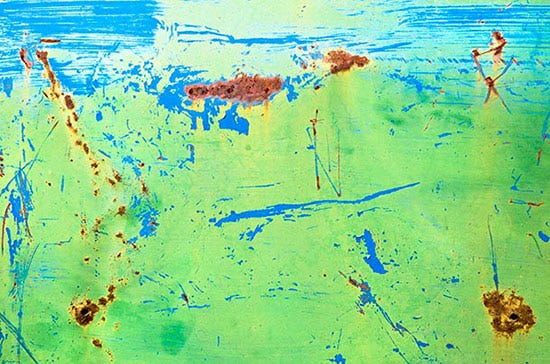

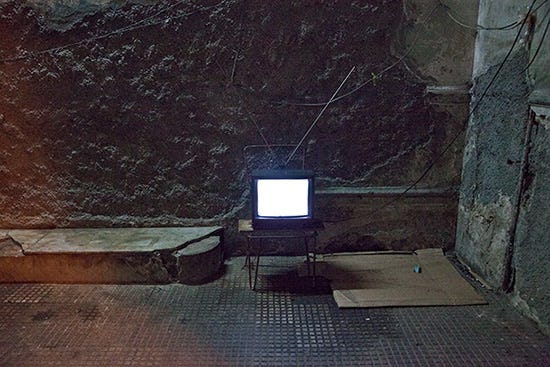

As an award winning photographer for more than 50 years she explored the world through photography with over 50 solo exhibitions and inclusion in twice that number of group and juried exhibitions. Lucinda had more ways of finding, seeing and making a photograph than Carter had ‘little liver pills’. Her vision was deep and wide as you can see from the few photographs I’ve posted here. Lucinda produced at least six books that I’m aware of. She was as prolific as she was excellent and original. I’ve seen enough of her work to know she could have created even more books from the rich archive she’s left behind.

As an editor and publisher at Fall Line Press we worked with her to publish her book Cuba. We were on a tight deadline to release for an exhibition she was having and she had enough compelling pictures to have doubled the size of the book. Her work was world class and as diverse and original as the life she lived.

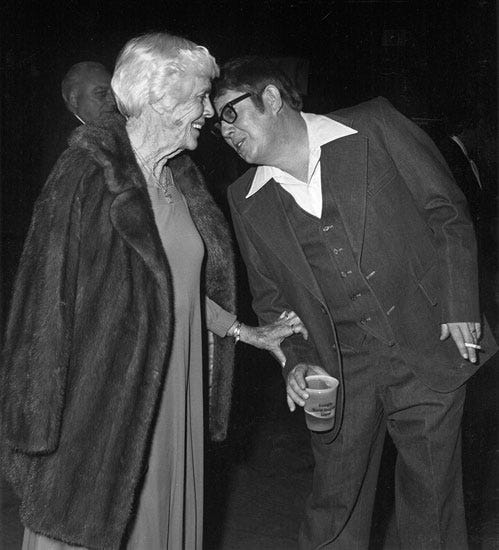

As a collector she shined brilliantly as well. She was an early, avid and astute collector. She began collecting when there was precisely one gallery in New York city devoted to photography. She hammered, with a smile and cocktails, Atlanta’s High Museum of Art to take up photography as a medium to collect. More than 1000 photographs she collected in the 70s and 80s were donated to The High, gifts that constitute the genesis of their outstanding collection. And she continued to support with collected and financial gifts The High throughout her life. I remember vividly seeing an exhibition of the early Nan Goldin work at The High that Lucinda had collected early on and gifted. Here she is standing in front of some of her many Brown Sisters by Nicholas Nixon - she acquired them all, one each year, and had no gaps the last time I checked.

Lucinda has been called the patron saint of photography in the south and there is real truth in that. I want to look here at three elements of how that happened. And inspired by her example, I ask what can we do to carry her successes forward. Volumes could be written about her photography, philanthropy and astute collecting and gifting. But, I want to turn here to an element of what I found most beautiful in Lucinda’s way of moving all the mountains she moved with her life in art.

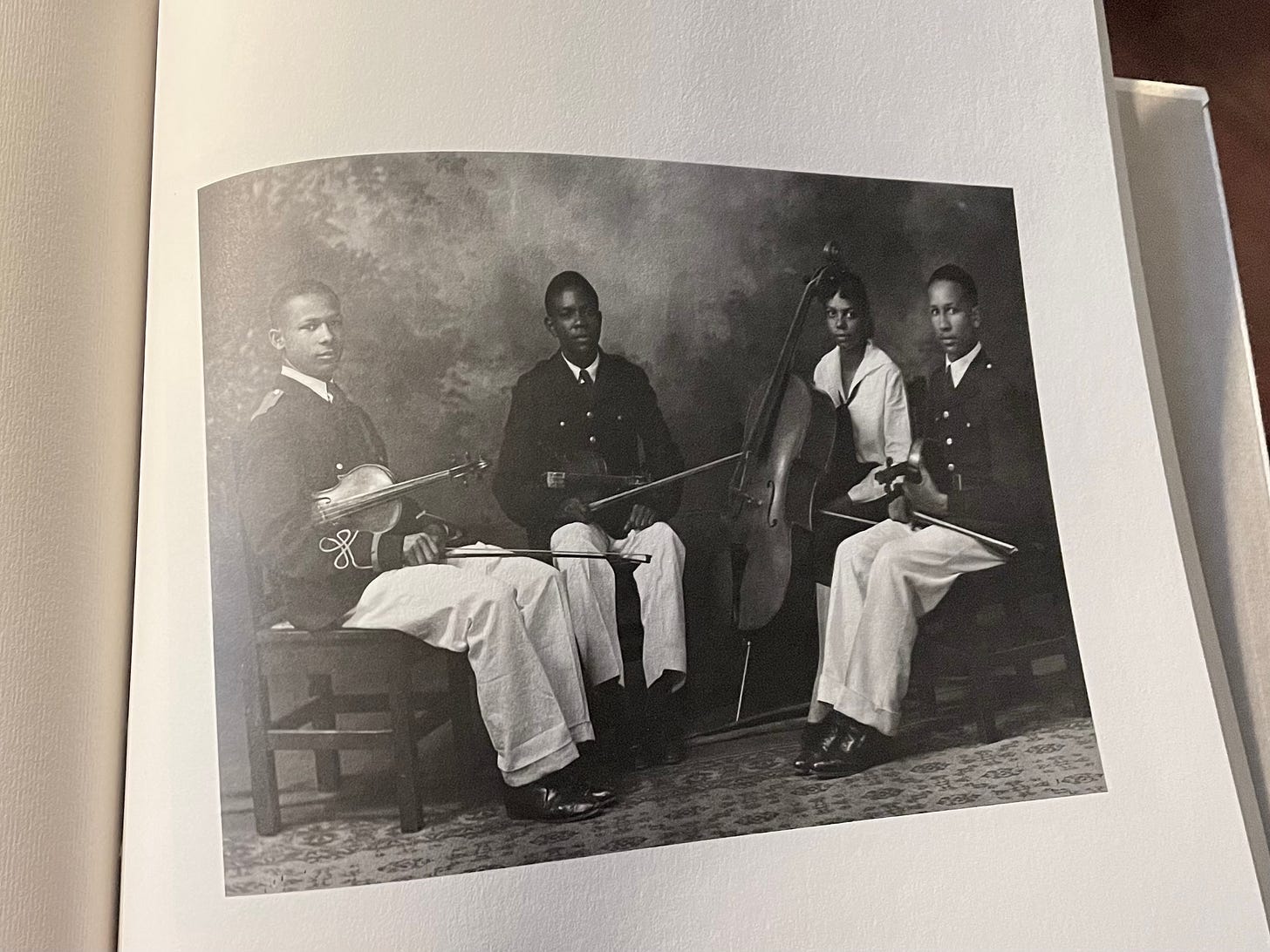

At 40 Lucinda discovered she was a photographer. Lucinda moved straightaway into it. She enrolled immediately in the first photography class taught at the Atlanta College of Art. And she became a serious photographer, student, collector and autodidact in the field - all at once. The first workshop listed in her resume was with Minor White in 1973 - that was the same year she co-founded Nexus. I take this as lesson number one from Lucinda. One is never too young or too old to embrace and commit fully to a new love or a deeper love of an old flame. By co-founding Nexus she helped lead Atlanta to becoming an important center of the art world’s rising love of creative printed matter - this was at an early stage of the movement when that really mattered. Here’s an image by photographer P. H. Polk that was included in the first photobook Nexus published. With an interview with Mr. Polk and a brilliant essay by Pearl Cleage it is one of the most beautiful books I’ve ever seen and the one of the most precious in my photobook collection.

My point here is that by the depth of her passion and personal engagement as an artist and photographer she generated inside of her existence an energy and resources that spilled over in a variety of ways that brought possibilities alive in the communities she cared about. She did not dawdle - she went immediately for the jugular. So think of Lucinda and remember her example if you feel it might be time to flame-on in some aspect of your life - don’t wait, don’t let age or some other ‘what about this’ get in your way. Go for it ferociously and relentlessly. Go flat out, don’t look back and don’t be bounded.

My second Lucinda lesson is to be of good cheer, have fun, weird out if that is where you need to be. I’m sure Lucinda could be cranky and pissed off - who isn’t sometimes. But, I never saw that. And in every encounter and situation that we shared together one on one or with others she was unflaggingly optimistic, positive and warm. I cannot even think of her without that engaging smile on her face and the possibility of a good laugh around the corner.

But Lucinda was born into a family with fortune and privilege you may say. That is certainly true and can be an advantage if you let it be. She certainly let it be. I’m guessing that for some wealth, good fortune and privilege might also get in the way, warp and create constraints or blindnesses about what is possible. I don’t think her good cheer and optimistic outlook were driven by the fact of her privilege, but by a kind of joy of living that was a flame she kept alive through connecting passionately with people and things she loved. There was a mountainous multitude of passions there for her. And this leads me to the last lesson I am bent on taking from Lucinda.

Put people first. Make your work about community and being a stand for individuals and groups that are your homies. Make everyone possible a homie. Give all you’ve got to give to lift up those you love and those you want to love. If you take a bold stand with a big smile and say ‘please come be with me and lets do something fun and great’, you will make friends and have community that will sustain you and them and all of us in ways that cannot be fully imagined when the dance first begins.

I want to end with a personal note to say that for me, the Lucinda experience has been and remains one of the best things that ever came my way. Here’s the thing. We talked photography and art and we collaborated on a book around some of her photographs from Cuba; we served on some arts boards together; I enjoyed some nice times at gatherings at her home and around Atlanta; but, for me, it was always more than that. Her example was in the back of my mind, asking in a corny kind of way - I wonder what Lucinda would think about that, do about that - how would she approach that. She was that smiling, badass, weirdo art shaman who made all my odd-ball ideas and bold undertakings seem doable. She inspired me to do more and be more. And in that sense Lucinda will be with me to the end. Her work lives on and all around me - but most of all as someone so beautifully said at our gathering - her hand print is on my heart and will always be there.

Closing out our time together Saturday, The Hambidge Center’s Director, Jaime Badoud, read for us a beautiful poem he’d written for the occasion speaking to what we were all feeling about Lucinda. And right in the middle of his elegy, a loud freight train passed nearby and he had to smile and relent a little as it passed through with a deafening roar. As it cleared out he then said what we were all thinking, ‘right on time’ - that’s Lucinda giving us a wink and a nod. She was not going to miss a good party with refreshments and friends! I felt her that day in the mockingbird’s song and hundreds if not thousands of us will carry her through our lives from now on. That is a comet’s tail that will shine on and on. At the end of the ceremony, it felt like it was just for me when guitarist, Eliot Bronson, stepped to the microphone and said ‘we’ll wrap up by singing this song Lucinda requested we sing together’: She’ll Be Coming Around the Mountain When She Comes. Its been a favorite of mine always - how did she know? She makes us feel that way. Good-bye Lucinda, we’ll see you soon - can’t wait for your next apparition.

Post Scriptum: I’ve reached out to a few friends for some other photos and materials about Lucinda and I’ll post a few of those along with Jamie Badoud’s poem in a shorter post later this week. If you know a friend of Lucinda’s please pass this remembrance along so we can share. Thanks. wb

Very inspiring message. I’m glad I read this today. The kick in the butt I needed to drown out all the voices in my mind telling me I can’t and keep going. Lucinda sounds like an incredible woman. Very sorry for your loss.

Beautiful remembrance